In my last Hilltown Postcard, I wrote about good neighbors. As promised, here is one about bad neighbors. The names have been changed for obvious reasons.

When we built our house and moved from one part of Worthington to another, we encountered a whole new group of neighbors. Just like in Ringville, we had good neighbors, many come to mind, but here we encountered a few bad ones.

What constitutes a bad neighbor? Frankly, the things they do just make them unlikeable. It’s a good practice to just stay clear after you figure that out like the neighbor who went off the deep end.

George used to be a decent friend before he became our next-door neighbor. Like us, he bought a piece of land and built the house he owned. Hank even worked with him. But things went strange between us, really strange.

Once when Hank went to George’s house to borrow a tool, he claimed our kids were breaking into his house. He said they moved his furniture, but only enough that he would notice. George was certain it was happening because he stuck a blade of grass between the front door and jamb, and it was gone when he got home. Hank stormed home in disbelief.

Then one of our sons caught George glaring at him through the woods.

Hank went to see the town’s police chief, who told him George had complained about our kids many times, but he didn’t believe any of it. The problem was solved when he sold his house and good neighbors bought it.

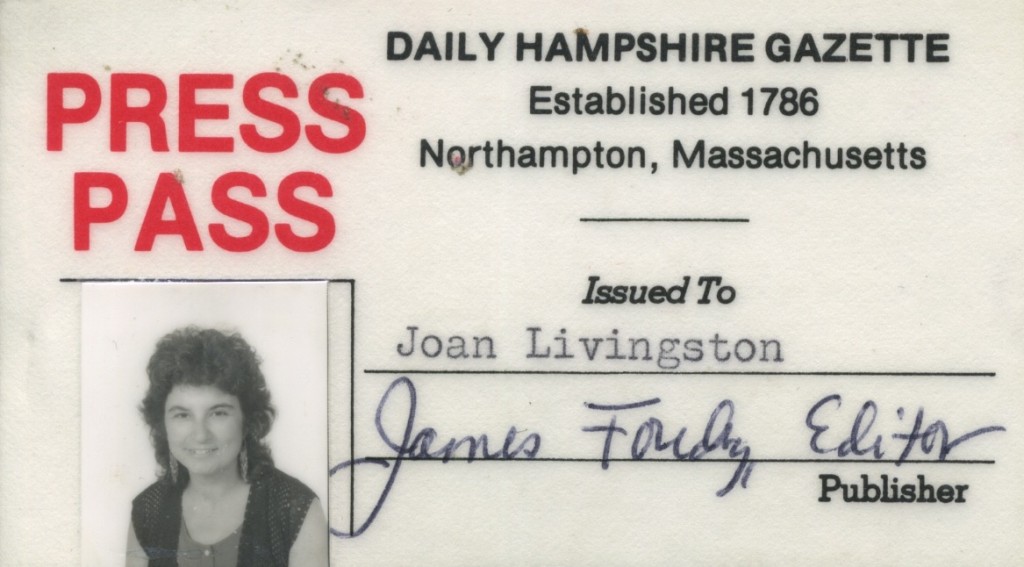

As the former hilltown reporter for the Daily Hampshire Gazette, I covered a few neighborhood disputes brought to a town board to be resolved. Most often the dissent concerned barking and/or vicious dogs their owners didn’t properly restrain although there was a notorious hearing involving pigs I wrote about earlier.

I can think of two dog situations in our new neighborhood, including one mutt that made it risky to walk along that part of the road in case the animal was loose. I recall a neighbor on a walk once flagged down a car and jumped inside for a ride home when that awful dog got loose.

Another neighbor had a Doberman Pinscher he didn’t tie up and we didn’t trust, with good reason it turned out, because the dog turned on the daughter. The man shot the dog, then left the body in the woods because the ground was too frozen to bury it. Wild animals picked the carcass clean. I recognized the tufts of fur when our dog dragged the bones to our yard. Anyway, the man moved away soon after that happened.

I recall a few incidents that get your head shaking when what a person does in private goes public. Ranking as the absolute worst was the creep who got arrested for watching his teenage daughter while she showered.

One time, we heard loud banging coming from a neighbor’s house. An ousted husband was repeatedly smashing the front end of his pickup against the door of a newly built garage. The cops were called.

Then there was the teenager who stole his mother’s car and crashed it in another part of town — an accident that badly injured him.

In another incident, a neighbor hooked up with the wrong people, thankfully very briefly.

One night Hank and I had finished watching the film, “Pulp Fiction,” when a state trooper knocked at the door and asked to use our phone since cell service was nearly nil in those days. It didn’t take much to get the trooper to say two men had gotten into a fight, and one guy, who happened to be a new friend of our neighbor Sandy, stabbed his buddy through the throat. The man had fled to the woods, and he was calling in dogs to find him. He would likely be going back to prison. He hadn’t been out that long. I believe he and Sandy might have been pen pals.

I thought for a moment I should tell the state trooper I was a reporter for the local newspaper, but I didn’t. I would instead pass the story to another reporter. The police dogs found the stabber hiding beneath the floorboards of a shed, and he was sentenced later to seven years after admitting in court he intended to kill his friend.

Sandy turned into a model neighbor, except for an occasional barking fit by one of her dogs, but they were harmless. Last I knew, she had a beautiful garden and worked hard at it.