My first writing tool was a pencil. The second was the black Remington typewriter you see in the photo above, a gift from my parents when I was just a girl beginning to write in elementary school. And recently, the machine returned to my possession.

The Remington no. 12 was built in Ilion, New York of steel and cast iron with a black enamel finish, so it’s a hefty machine. My research indicates the typewriter probably was built in the 1920s, a direct descendent of the 1874 Shoals & Glidden typewriter, which was the first commercially successful typewriter.

I have no clue where my parents, who were excellent foragers, found the typewriter. But they did when I was attending a creative writing class, where I learned as a fifth-grader about such things as metaphors and similes. The class’s teacher, Donald Graves called my parents to say he was impressed with the maturity of my writing.

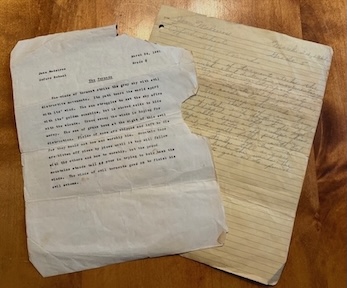

I wonder if Mom and Dad were inspired to find the typewriter or it was just a coincidence. I still have two copies of a short piece, The Tornado, I wrote. As you can see, the original was handwritten. The second was typewritten on the Remington.

Here’s how that piece begins: The winds of torment strike the grey sky with evil destructive movements. Its path tears the world apart with its wind. The sun struggles to set the sky afire with its golden sunshine, but is shoved aside to hide with the clouds.

I used the Remington for creative writing and school assignments until I went away to college and my generous Aunt Ernestina gave me a lightweight portable Smith Corona. I had been expecting to lug that heavy machine with me. Of course, I eventually moved onto to computers.

But I never forgot my Remington. I knew it had to be somewhere in my parents’ home because they never threw anything away — a challenge now as we clean out the house before it goes on the market. My sister-in-law found the typewriter in the back of a closet upstairs. Thanks, Patty.

The machine has accumulated decades of dust, which I plan to carefully remove. I will need to replace the ribbon — the spools are accessible by doors on each side of the frame. Everything about my Remington works. Yes, it is a well-constructed machine.

Will I actually use the typewriter again to write? Maybe or maybe not, but it will have a place of honor in my writing spot.

Pressing the keys and sliding the lever, I think of how many classic books I’ve enjoyed that were likely written on a similar machine.

When I visited author Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ home in Cross Creek, Florida I saw the typewriter she used to write The Yearling and other books. Her home, which is now a state park, had most everything she owned carefully placed in the rooms as she left them before she died in 1953. My favorite was the screened-in porch where she wrote on a similar typewriter.

Interestingly, a black Remington typewriter is an important prop in the Young Adult novel I’ve written, The Talking Table. It is set in 1967. The story is told by Vivien Winslow, who is 15. Her father, who is a famous author, used a similar typewriter he found abandoned on a sidewalk. Eventually, in a fit of frustration, he threw it in the Charles River in Boston, where he lives. But then he finds another typewriter.

While I was writing those scenes, I thought of my own Remington 12. I just couldn’t let it go, and happily, I now have it back.

P.S. Thanks to all of you who read my most recent post, When I Used to Be a Poet. It was a record number for me.